“Disabled Life”

For this article, I was asked to write about “living with a disability.” According to the CDC, over 61 million adults in the United States live with a disability. That means roughly 1 in 4 adult Americans cope with some form of disability daily. A portion of these individuals have a visible disability, or one that can be seen with the naked eye. Others, such as myself, have an invisible disability.

Invisible disabilities, also known as hidden disabilities, can best be defined as a collection of unforeseen challenges, primarily neurological in nature. Symptoms such as chronic pain, extreme fatigue, and cognitive dysfunction can all be classified as invisible disabilities. Because these symptoms are not obvious to the onlooker, people with invisible disabilities can be accused of faking or falsifying their disability claim. As a result, those with hidden disabilities can become alienated and withdrawn from society.

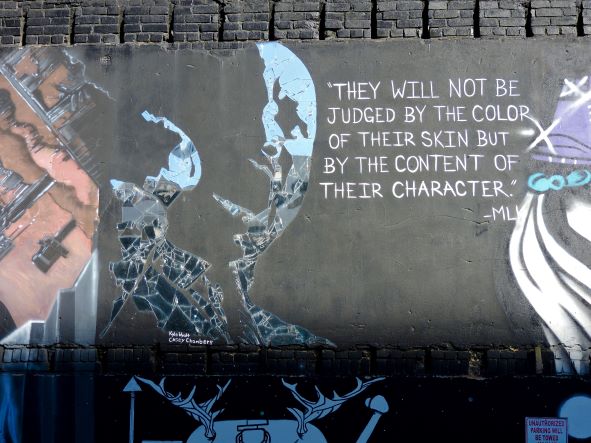

Unfortunately, many of you reading this article have likely experienced some form of disability discrediting. Perhaps that is what has driven you to visit this website in the first place. Regardless of motivating factors, it is imperative that we come to the consensus that any form of disability shaming is completely unacceptable.

Living with a disability is hard enough without others judging what constitutes an individual to be disabled. According to the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 (ADA) an individual with a disability is a person who: Has a physical or mental impairment that substantially limits one or more major life activities; has a record of such an impairment; or is regarded as having such an impairment. Ultimately, no further distinction needs to be made.

But how do we respond when someone questions our disability?

I recently had to answer this question when an individual doubted my disability because it did not match the definition of what she considered to be disabled. After suffering a traumatic brain injury (TBI) in 2013, I was diagnosed with multifactorial cognitive dysfunction. Since my disability stems from my brain, it falls into the realm of an invisible disability. Furthermore, I also suffer chronic migraines, another symptom of my disability that can not be seen. Given the totality of circumstances surrounding my disability, coupled with the fact that I recently published a book, said individual stated, “I could not accomplish such a task and still call myself disabled.”

Upon hearing this, I immediately wanted to advocate for myself and verbally retaliate. However, I quickly realized that arguing with somebody so uninformed would get me nowhere. Instead, I simply stated that “my disability did not equal an inability.” Meaning, that despite the debilitating symptoms stemming from my TBI, I would not allow said symptoms to distinguish my ability to complete a daunting task. Instead, I adapted to work around my cognitive dysfunction and chronic migraines to create my own path to publication.

I believe adaptation is key to thriving with a disability. Because we are told that we can’t do a certain thing, doesn’t mean we can’t find another way to complete the task at hand. I believe disabled individuals are some of the most adaptable on the face of the planet. The ability to adapt should be viewed as a strength, not a means to question one’s status as a disabled person.

Let’s utilize writing this article as an example. Because of my cognitive dysfunction, I typically forget what I am writing prior to constructing the next sentence. This causes me to constantly re-read prior sentences before I’m able to add to my existing work. Overall, this makes writing a very tedious and sometimes frustrating process. However, instead of giving up on my dream of writing published works, I’ve learned to adjust to the “new normal” that having a disability has created. One of the ways I’ve adopted to overcome some of the symptoms associated with my disability is by setting obtainable goals.

Since it is no longer feasible for me to sit down and write thousands of words in a day, I’ve learned to alter my expectations to match my projected output. Instead of a few thousand words, I aim to write a few hundred words per sitting. Once I’ve constructed one well developed paragraph, I transition to the next. I do not focus on the word count, but rather writing the most compelling sentence that I can construct. I view each finished sentence as a small victory; something I can build from.

By celebrating the small victories, I gain the confidence it takes to tackle something greater.

I imagine this is how many other disabled individuals also cope with their unique disabilities. Through the process of adaptation to overcome, paired with setting an obtainable goal, insurmountable tasks no longer seem so daunting. Once a portion of the assignment is complete, it frees the individual to focus on the remaining segments of the project at hand. Each leftover hurdle can be analyzed and a plan to overcome it can be fashioned.

The recovery concept of “taking one step at a time” is something I’ve applied countless times since becoming disabled. I used to get extremely frustrated with myself when I could no longer perform a task the way I once did or envisioned that I could.

Today, I am more kind to myself. I do my best not to get upset when I immediately can’t offer a solution to something that is asked of me. Instead of getting frustrated or feeling defeated, I ask for the additional time I need to troubleshoot the problem at hand. Setting a realistic timeframe based on my needs helps ensure that I’m given the best chance to complete the task. I’m no longer afraid to advocate for what I require to be successful and that has helped me find more success. As I build off those successes, I reacquire the self-confidence it takes to attempt something I haven’t completed, or even failed at in the past.

But what happens when I’m asked to do something that I know I’m not capable of completing?

If a task appears to be outside my skillset, I’ve learned to immediately ask for assistance. I used to spend precious time and energy trying to complete the task on my own, and that typically lead me down a path of disappointing failures.

While it’s not always the worst thing to try and fail, compounding failures can become disheartening over time. Instead of being prideful and placing all the responsibility upon myself, I’ve discovered that delegating unmanageable assignments can be the most productive use of my time. By becoming a better manager, I’ve been able to redistribute responsibilities to those best suited to tackle the issue at hand. Managing my time and talent helps place me in the driver’s seat of life and make decisions that positively impact myself and others. Another factor that has helped manage my disability tremendously is increased communication.

I no longer allow myself to suffer in silence.

Aside from learning the thresholds associated with my disability, I’ve also learned how to effectively discuss how I am feeling. Instead of simply stating “I’m sick” or “I don’t feel well,” I aim to define my symptoms to the best of my ability.

Take chronic migraines as an example. I used to believe migraines were nothing more than a horrible headache until I began experiencing them. Once I became familiar with all the debilitating symptoms associated with migraines, I was better able to describe to others what experiencing a migraine felt like. By using the proper descriptive terms, I was able to create imagery that also encouraged others to recognize what transpired while I was suffering a migraine. Through creating a shared understanding of one of the contributing factors of my disability, I found individuals to be more compassionate to my overall situation. This newfound empathy allotted more time to focus on healing and less time spent persuading others I was struggling. Overall, it’s been a relief to know that those closest to me can relate to my situation.

Another way I’ve been able to cope with living as a disabled individual is through reframing my story. I used to feel that becoming disabled took something, or some part, away from me. Today, I view things differently.

Instead of seeing my disability as weakness, I consistently try to reframe it into a strength. Reframing, also known as cognitive reframing, is a practiced technique used to change one’s mindset to view a situation, relationship, or person from a fresh perspective. Cognitive reframing is something an individual can do on their own when thought patterns have become negative or distorted. For example, I have become a better writer due to my disability because it has allotted me the time to focus and hone my craft. Had I not become disabled, I likely would have never had the free time I took to grow from an average writer into a published author.

The essential idea behind reframing is the way, or “frame,” through which one views a situation shapes his or her viewpoint. When the frame is shifted, the overall message changes. The reinterpreted message is often accompanied by a change in thinking. Changing the way one thinks, may also alter the way one behaves or responds to a particular act or situation. Overall, whether cognitive reframing is practiced independently or with the help of a licensed counselor, it can be a helpful way of turning negative thought or dilemma into an opportunity for growth.

Overall, I’ve talked a fair amount about what being disabled has meant to me. Together, we’ve examined the differences between a visible and invisible disability, and how the designation can impact the way others view somebody with an invisible disability. I’ve shared how disability discrediting can create feelings of alienation or make disabled individuals withdraw from society. Furthermore, I’ve shared how one can respond when someone chooses to question his or her disability.

As opposed to getting upset or verbally retaliating, I have benefited from explaining that a disability does not always equate to an inability. Instead of arguing the definition of being disabled, I focus on how adaptable many disabled individuals have become. Countless individuals have found innovative and creative ways to work around their disabilities and the related symptoms. These people deserve praise, not to have their disability questioned.

Another concept that was discussed is setting obtainable goals. By setting a reachable goal, we can build momentum toward completing tasks that have otherwise seem impossible or completely out of reach. Building on small successes also helps increase one’s overall feeling of self-worth. This can lead to increased self esteem and the overall drive to tackle something greater.

I also dove into what I do when I’m tasked with something I know I’m not capable of completing. Asking for help in these situations has become second nature, and I’m no longer embarrassed to admit when I need assistance. Overall, I’ve found I’m happier when I advocate for what I need, as opposed to attempting to struggle through an unreasonable situation. Ultimately, I believe others are prone to help when they are asked and recognize somebody needs assistance.

Finally, we discussed communication and reframing. By having conversations about the symptoms surrounding my disabilities, I’ve allowed those close to me to gain a better understanding of the obstacles I face daily. Increased understanding has brought an increased level of empathy into my life. Having others be empathic to my situation helps me stay positive, especially on the more challenging days.

I also utilize reframing of thoughts to aid in altering my perception and the way I approach life. Through viewing once negative messages, as neutral, or better yet positive, I’m able to adjust my attitude and my actions. It’s easy to get locked into the mindset that one’s outlook is the only perspective from which a problem can be viewed. Reframing creates a new world of fresh possibilities while helping displace negative thought patterns.

Overall, I hope you found value in reading this article. Despite the vast differences in what makes each of us disabled, I believe there are common factors that impact each of us on a frequent basis. It’s my hope that by sharing how I’ve dealt with some of these aspects, others may find value in my methodology. Ultimately, I believe we are all incredible, resilient individuals who consistently find a way to adapt and overcome our unique situations.

To continue this discussion, or propose a topic of your own, please visit the forum page. Thank you all for taking a few minutes to advance the conversation of what it’s like to live with a disability.

About the author:

Travis Sackett has been living as a disabled individual since suffering a traumatic brain injury in 2013. He recently published a recovery memoir, My Life with Karma, which explores the events of his life which left him addicted, caught in a cycle of substance abuse, and jaded by a system that chews people up and spits them out. Despite these difficulties, Travis tells the tale of how the unconditional love of a rescue dog can be a catalyst for meaningful change. My Life with Karma is available through Amazon, Barnes & Noble, and Scribd.